The Daily Constitutional, (North Yarmouth, Maine) 40"x30," Not currently for sale.

A Blending of Two Worlds, 8x10," acrylic study on canvas, privately owned

Landscapes:

The Field Is White, Already to Harvest (Prince Edward Island, Canada), 18x24", Privately owned

Spicy Air of Dusk, 8x10," Antimony, Utah, email for pricing

Home to Be Milked at Toot's (North Yarmouth, Maine), 9x12," privately owned

Antimony, Utah, 8x10," privately owned

The Sacrifice, 18x24" privately owned

(Details)

Fiddlehead Serenade, 9x12," privately owned

Fireweed, 9x12," privately owned

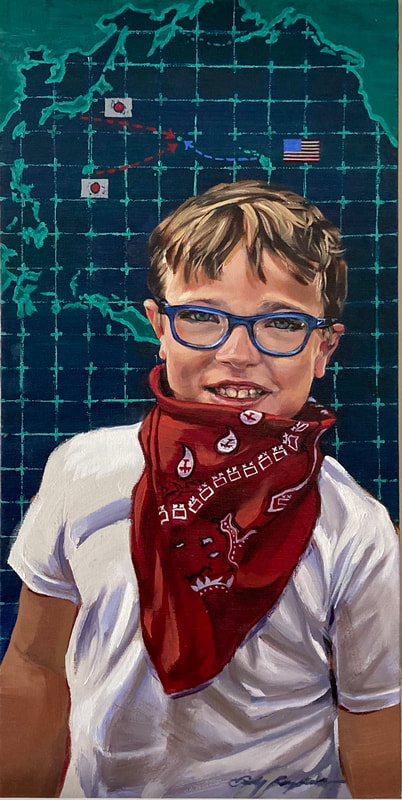

Ever After, I Knew, 24x18," Privately owned

The above painting, entitled, Ever After, I Knew, depicts the following account shared by my children's great-great-great grandfather, Joseph F. Smith (pictured as the young boy at left):

In the fall of 1847 my mother and her brother, Joseph Fielding, made a trip down the Missouri River to St. Joseph, Missouri, about fifty miles, for the purpose of obtaining provisions and clothing for the family for the coming winter, and for the journey across the plains the following spring. They took two wagons with two yoke of oxen on each. I was almost nine years of age at the time, and accompanied my mother and uncle on this journey as a teamster. The weather was unpropitious, the roads were bad, and it rained a great deal during the journey, so that the trip was a very hard, trying and unpleasant one. At St. Joseph we purchased our groceries and drygoods, and at Savannah we laid in our store of flour, meal, corn, bacon and other provisions.

Returning to Winter Quarters, we camped one evening in an open prairie on the Missouri River bottoms, by the side of a small spring creek which emptied into the river about three quarters of a mile from us. We were in plain sight of the river and could apparently see over every foot of the little open prairie where we were camped, to the river on the southwest, to the bluffs on the northwest, and to the timber which skirted the prairie on the right and left. Camping nearby, on the other side of the creek, were some men with a herd of beef cattle which they were driving to Savannah and St. Joseph for market.

We usually unyoked our oxen and turned them loose to feed during our encampments at night, but this time, on account of the proximity of this herd of cattle, fearing that they might get mixed up and driven off with them, we turned our oxen out to feed in their yokes. Next morning when we came to look them up, to our great disappointment our best yoke of oxen was not to be found. Uncle [Joseph} Fielding and I spent all morning, well nigh until noon, hunting for them, but to no avail. The grass was tall, and in the morning was wet with heavy dew. Tramping through this grass and through the woods and over the bluff, we were soaked to the skin, fatigued, disheartened, and almost exhausted.

In this pitiable plight I was the first to return to our wagons, and as I approached I saw my mother kneeling down to prayer. I halted for a moment and then drew gently near enough to hear her pleading with the Lord not to suffer us to be left in this helpless condition, but to lead us to recover our lost team, that we might continue our travels in safety. When she arose from her knees I was standing nearby. The first expression I caught upon her precious face was a lovely smile which, discouraged as I was, gave me renewed hope and an assurance I had not felt before. A few moments later Uncle Joseph Fielding came to the camp, wet with the dews, faint, fatigued, and thoroughly disheartened. His first words were: “Well, Mary, the cattle are gone!”

Mother replied in a voice which fairly rang with cheerfulness, “Never mind; your breakfast has been waiting for hours, and now, while you and Joseph are eating, I will just take a walk out and see if I can find the cattle.”

My uncle held up his hands in blank astonishment, and if the Missouri River had suddenly turned to run upstream, neither of us could have been much more surprised. “Why, Mary,” he exclaimed, “what do you mean? We have been all over this country, all through the timber and through the herd of cattle, and our oxen are gone– they are not to be found. I believe they have been driven off, and it is useless for you to attempt to do such a thing as to hunt for them.”

“Never mind me,” said Mother; “get your breakfast and I will see,” and she started towards the river, following down spring creek. Before she was out of speaking distance the man in charge of the herd of beef cattle rode up from the opposite side of the creek and called out: “Madam, I saw your oxen over in that direction about daybreak,” pointing in the opposite direction from that in which Mother was going. We heard plainly what he said, but Mother went right on and did not even turn her head to look at him. A moment later the man rode off rapidly toward his herd, which had been gathered in the opening near the edge of the woods, and they were soon under full drive for the road leading toward Savannah and soon disappeared from view.

My mother continued straight down the little stream of water until she stood almost on the bank of the river. And then she beckoned to us. I was watching her every movement and was determined that she should not get out of my sight. Instantly we rose from the “mess-chest” on which our breakfast had been spread and started toward her. And like John, who outran the other disciple to the sepulchre, I outran my uncle and came first to the spot where my mother stood. There I saw our oxen fastened to a clump of willows growing in the bottom of a deep gulch which had been washed out of the sandy bank of the river by the little spring creek, perfectly concealed from view. We were not long in releasing them from bondage and getting back to our camp, where the other cattle had been fastened to the wagon wheels all the morning. And we were soon on our way home rejoicing.

(Smith, Life of Joseph F. Smith, pp. 131-33)

Canvas print pricing list available via e-mail inquiry at [email protected]. 10% total discount given to descendants of

Joseph F. Smith who, upon ordering, use the phrase,“Yes siree; dyed in the wool; true blue, through and through!”

Portraits and Figures

Precious Above All, 11x14," privately owned

1) Knowing It, 12x24," Privately owned

2) The Lioness, 12x24", privately owned

3) Golden Night, 12x24", privately owned

4) Snow Cherub, 12x24", privately owned

2) The Lioness, 12x24", privately owned

3) Golden Night, 12x24", privately owned

4) Snow Cherub, 12x24", privately owned

Looking into Her Future, 9x12", privately owned

A Fisher of Men, Privately owned

First Remembered Christmas, Privately owned

The Fairy Godmother, privately owned

One Left to Go, 9x12", privately owned

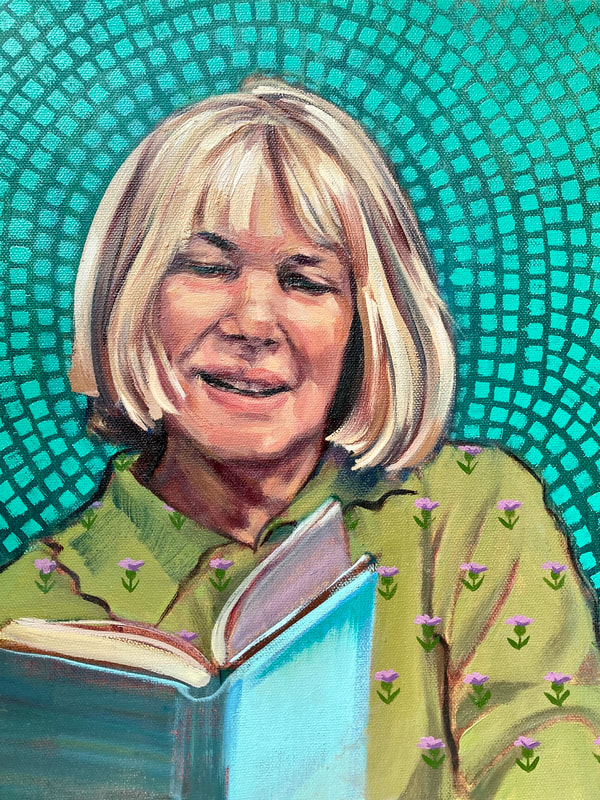

Down a Rabbit Hole with Jack, 9x12," privately owned.

I'm not currently taking on new commissions in 2024, opening my schedule to finish the

second draft of my novel before my 50th birthday in September. Wish me luck! Actually, I need more than luck--I need time!

Check back occasionally for any

stock pieces I may highlight here, available for purchase. And...most importantly, best wishes with your own

artistic endeavors, friends! Happy reading, writing, painting, or creating--however you do it!

© 2019 Emily Reynolds/ All rights reserved